The Ultimate Whiskey Guide: Everything You Need to Know!

WELCOME TO WHISKEY

If you're a casual cocktail drinker you probably think whiskey is just another liquor that can bring on the tipsy — Jack and Coke just about covers it, right? No. That's wrong. Very wrong. So wrong, in fact, we're going to have to spend the next 8,000 words going ice balls-deep into some whiskey education (with some sexy infographics!) so you can hold your own if this topic ever comes up at the bar. And don't come at us with that I can just look at the wiki for all this talk; we've cherry-picked all the crucial points you'll need to know, and put everything together into one very smooth, albeit long sip of information. In the following Ultimate Whiskey 101, we'll be talking about Bourbons, Scotches, Rye whiskey, Irish whiskey, blended vs. single, malt vs. grain, where the various whiskeys are from, how whiskey is made, how to drink whiskey, how whiskey flavors break down, how whiskey nomenclature works, whiskey aging, when to spell it "whiskey" and when to spell it "whisky" — by the time you're through with this post you'll be able to put "passed Tipsy's whiskey course" on your résumé. So buckle up, people. It's time to take a seriously deep dive into the world of whiskey; don't worry about holding your breath though, the water of life tastes fine. https://giphy.com/embed/vwKR47U8PvY1qWHAT IS WHISKEY?

The most succinct, technically correct definition of whiskey you'll find on the internet is that it's a distilled alcohol made from fermented grain mash. Which means that some type of grain — such as barley, corn, wheat, etc. — has been taken, encouraged to grow (or germinate) by being wetted, had its growth halted by being dried, then combined with yeast in order to turn the soluble sugars (produced by the grains' stunted growth) into alcohol — specifically ethanol. The real interesting part about whiskey, however, is in its distillation process and how it's aged. Once the alcohol produced from the fermentation process is produced, that could theoretically become other types of consumable booze, such as beer. But with whiskey, after the alcohol has been fermented, it is distilled in copper stills, often multiple times, which increases its alcohol by volume (ABV). The concentrated alcohol is then put into barrels where it usually sits for years. As the whiskey sits in the barrels, it interacts with the flavorful wood via chemical interactions. The ethanol in the whiskey (which is a solvent and also the compound that gets you tipsy) dissolves the wood and picks up various flavor compounds from it, such as whiskey lactones, which tend to give whiskey a woody, coconut flavor. Over time the alcohol takes on an array of the wood's flavors by dissolving various chemicals, and also develops its distinctive brownish caramel color, as some of the chemicals the ethanol dissolves affect pigment. (Side note: Sometimes caramel coloring additive gives the whiskey its color, but that's not really all that classy.)

Once the whiskey has been aged — which can happen over a couple of years, or even 57 years in the case of this Glenfarclas Single Malt Scotch — it's ready to be blended with other whiskies, water, or taken as is, and bottled. And bang, you have yourself some drinkable whiskey.

As the whiskey sits in the barrels, it interacts with the flavorful wood via chemical interactions. The ethanol in the whiskey (which is a solvent and also the compound that gets you tipsy) dissolves the wood and picks up various flavor compounds from it, such as whiskey lactones, which tend to give whiskey a woody, coconut flavor. Over time the alcohol takes on an array of the wood's flavors by dissolving various chemicals, and also develops its distinctive brownish caramel color, as some of the chemicals the ethanol dissolves affect pigment. (Side note: Sometimes caramel coloring additive gives the whiskey its color, but that's not really all that classy.)

Once the whiskey has been aged — which can happen over a couple of years, or even 57 years in the case of this Glenfarclas Single Malt Scotch — it's ready to be blended with other whiskies, water, or taken as is, and bottled. And bang, you have yourself some drinkable whiskey.

A BRIEF WHISKEY HISTORY

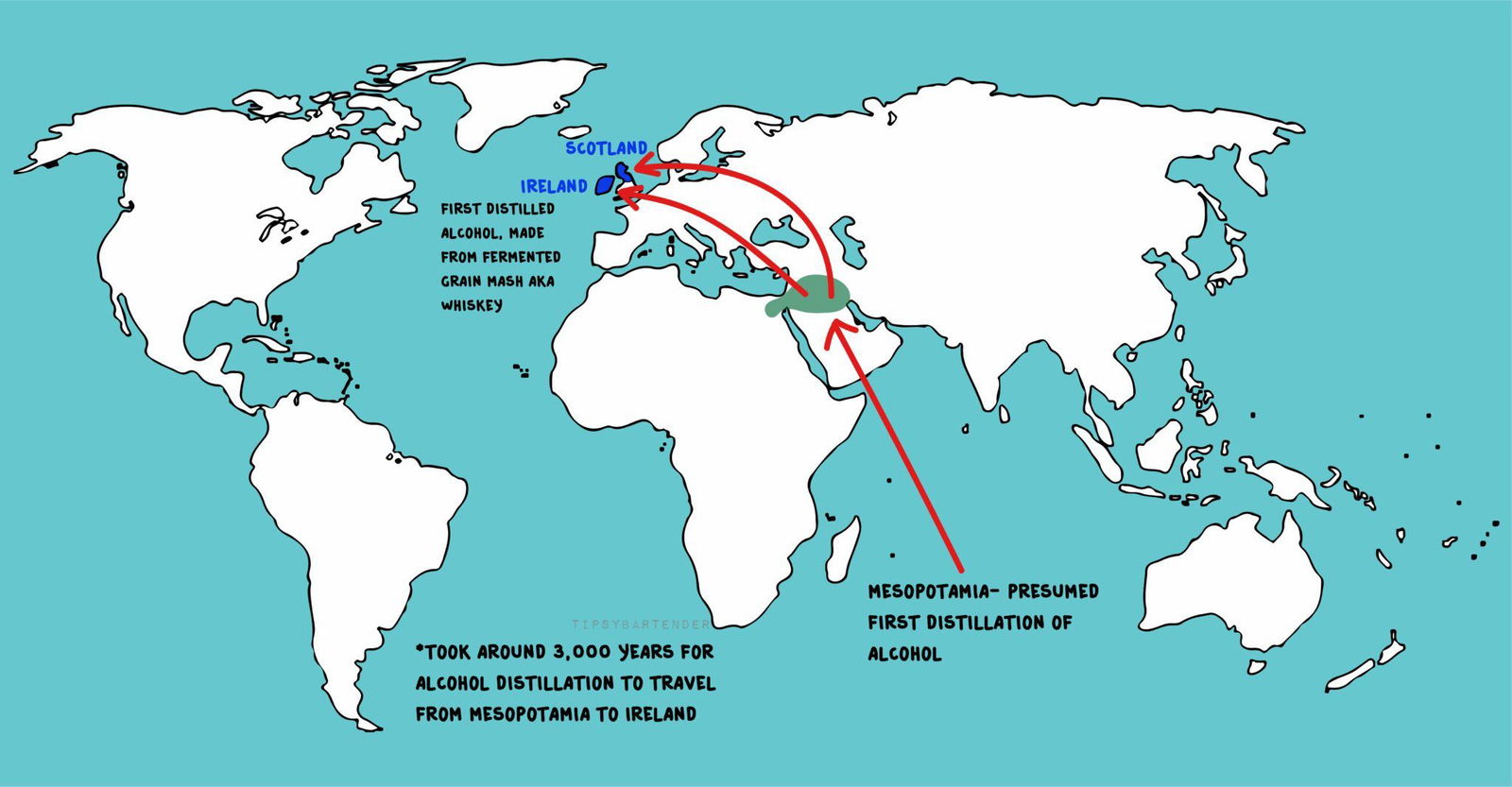

Now that we have the definition down, here's a brief history of this institutional distilled spirit made from fermented grain mash. The story of whiskey goes back more than a 1,000 years, but in the following snapshot we're only tackling a handful of the most crucial highlights from the millennium, especially those relevant to American history.10th and 11th Century AD: First Appearance in Scotland and Ireland

Although the first distillation of alcohol is believed to have taken place in Mesopotamia around 2,000 BC (in order to make perfumes though, not booze), making whiskey out of alcohol really began 3,000-3,200 years after that in Scotland and Ireland. As itinerant monks began to spread distillation processes from mainland Europe to monasteries in Scotland and Ireland, they had to find fermentable substitutes for grapes, which were only prevalent on the continent. Consequently, they turned to widely available grains, and the origins of whiskey were born. (Side note: Both Ireland and Scotland like to claim that whiskey originated in their respective countries, although it seems that neither country can claim definitive proof.)

Early 15th Century: First Written Record of Whiskey

The first written account of whiskey as a unique liquor was recorded in an early 17th-century text called the Annals of Clonmacnoise, which translated a lost Irish chronicle into modern English. In the Annals, translator Conall the Historian notes that "Richard or Risdard maGranell, cheiftaine of Moytir-eolas, died at Christmas by takeing a surfeit of aqua vitae, to him aqua mortis." Aqua vitae was a term used in the middle ages and Renaissance periods to describe distilled alcohol. It was a recycling of the eponymous archaic Latin term, which also described distilled spirits. Also, yes, the first time whiskey is ever mentioned in writing, it was because it killed a dude.16th Century: Whiskey Production Moves Out of Monasteries and into the Mainstream in England

After King Henry VIII of England — you know, the guy who had a bunch of wives and declared a king's sovereignty over the church 'cause it wouldn't give him an annulment — was excommunicated by Pope Paul III in 1538, he abolished the church's monasteries, sending a whole bunch of monks out into the world with knowledge of how to make whiskey and no jobs. To make a living, these monks began producing whiskey in their own homes, and using the yields from their own farms, resulting in whiskey being made available to the general public.

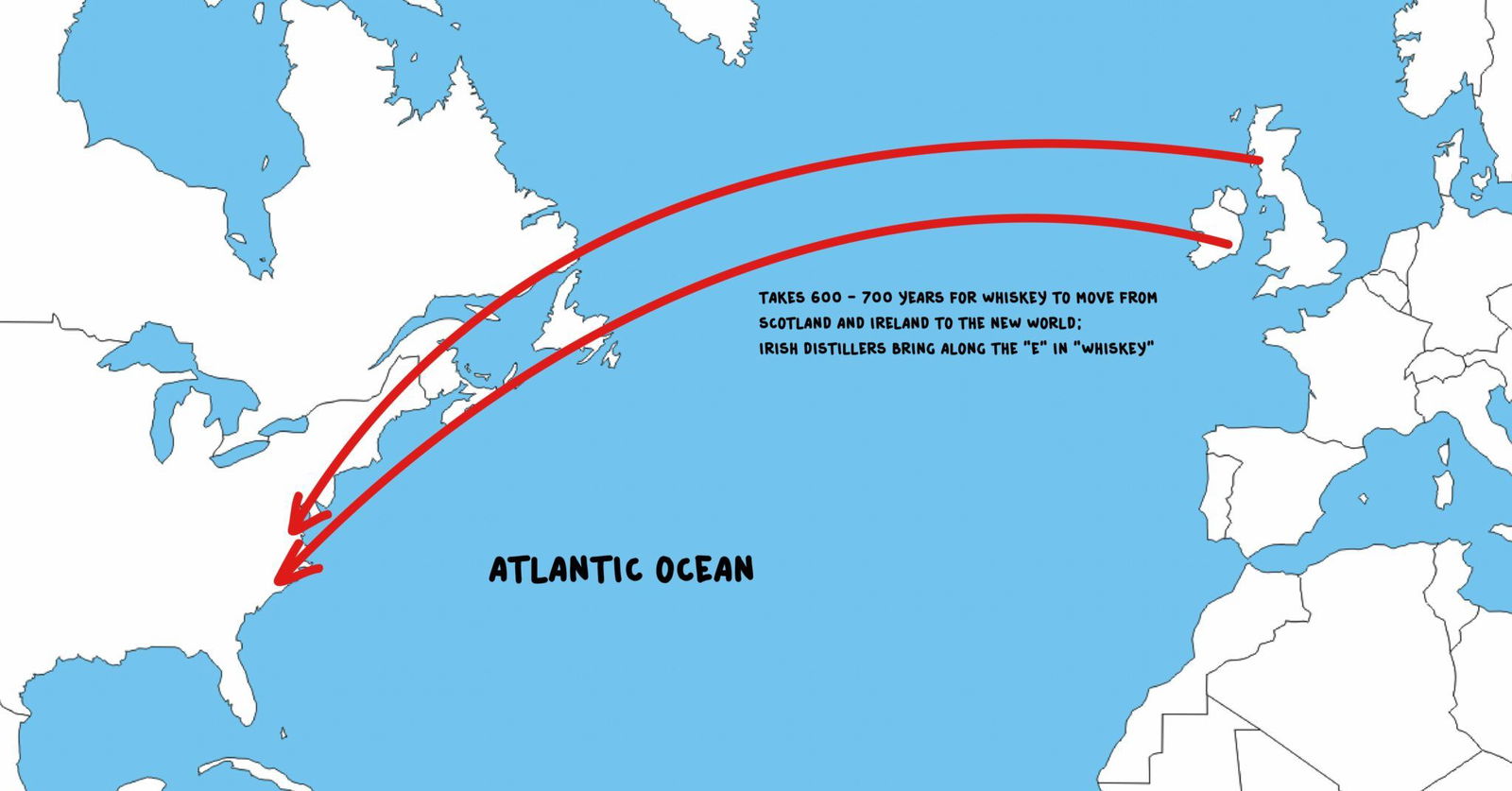

17th Century: Whiskey Comes to the New World

During this period European colonists began to arrive in America, and brought along with them their whiskey distillation knowhow. Scottish and Irish immigrant settlers also started to set up their own distillation operations with the New World's grains.

18th Century: The English Malt Tax of 1725, Moonshine, and Whiskey as American Currency

Back in Europe, England and Scotland were joined together under The Acts of the Union. After the union, taxes were raised substantially, which included the English Malt Tax of 1725. This tax forced Scottish distillers to make their whiskey covertly, at night when smoke from their stills could be hidden in darkness. The term "Moonshine," which originated in Britain in regards to various illicit activities undertaken at night, would be applied to whiskey in this context. (Side note: At the beginning of the 19th century, at least half of Scotland's whiskey output was illegal.) https://giphy.com/embed/TfPyPuQQWKfNS In America, toward the close of the 18th century, whiskey actually became used as a currency as in the post-Revolutionary War period money became scarce. Many farmers turned their corn into whiskey, and used it as a form of monetary exchange in order to speed up their migration to the West. In 1791, the newly formed U.S. government under the administration of George Washington — who eventually built his own distillery at Mount Vernon, VA pumping out 1,000 gallons a month — levied a tax on whiskey. This resulted in the Whiskey Rebellion, which saw farmers rise up against the government in opposition to the tax, although it was quickly suppressed by Washington himself leading an army of 13,000 militiamen.

George Washington leading militiamen against the Whiskey Rebellion. Image: Wikimedia / Frederick Kemmelmeyer

19th Century: An End to Scottish Moonshine

Back in Scotland and England, the UK government passed the Excise Act of 1823, which legalized distillation of alcohol for a more reasonable fee. Subsequently, Scottish Moonshine production was effectively ended.20th Century: Prohibition in the U.S., "Medicinal" Whiskey, and the Branding of Bourbon as America's Official Whiskey

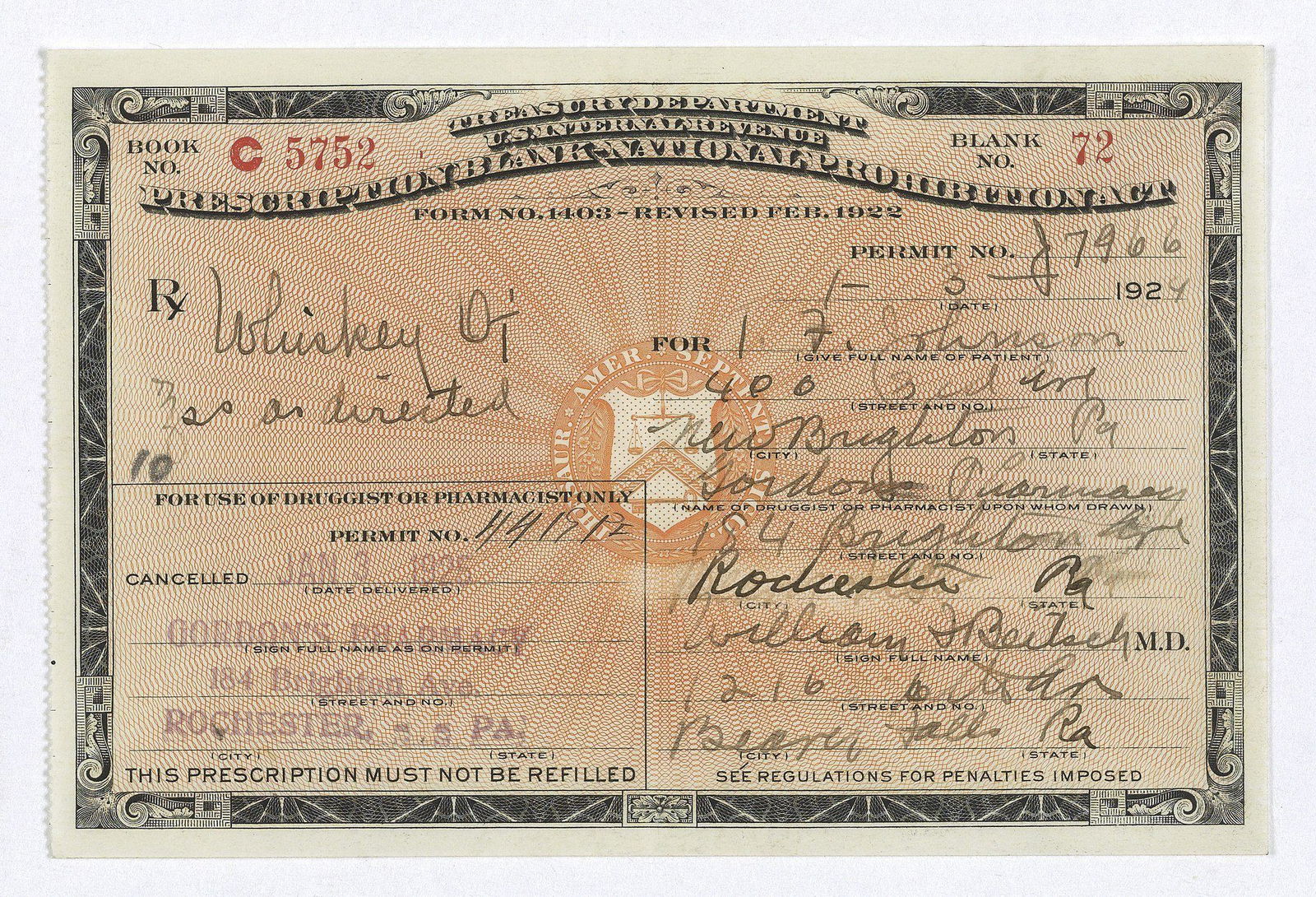

With the establishment of the 18th Amendment in 1920, prohibition of all alcoholic beverages was put into place until 1933. An exception was made for medicinal whiskey, however. (Side note: This helped out the Walgreens pharmacy chain, which grew from 20 stores to nearly 400 during this period.) https://giphy.com/embed/l2oeeiWRIfeqfO6cse Then in 1964, Congress passed legislation declaring bourbon “a distinctive product of the United States,” and effectively gave the U.S. its own whiskey type that could only be produced on American soil. Prohibition-era prescription for whiskey. Image: Wikimedia / U.S. Treasury Dept.

Prohibition-era prescription for whiskey. Image: Wikimedia / U.S. Treasury Dept.

WHISKEY VS. WHISKY: WTF IS UP WITH THIS SPELLING?

Location, location, location: That's what "Whiskey" vs. "Whisky" boils down to. Basically, whisk(e)y makers in the U.S. and Ireland spell whisk(e)y with an "e," whereas Scotland, Japan, and Canada drop the "e." A quick rule of thumb for remembering which countries spell whisk(e)y with an "e" is to note that both Ireland and America have an "e" in their names. So if the country has an "e" in its name, then so does its whisk(e)y. Canada, Japan, and Scotland, which don't have an "e" in their names, don't include the "e." https://giphy.com/embed/1zJYRmrT54B30gjSdN Note that there are exceptions to this rule of thumb, however. E.g. both Maker's Mark and George Dickel, two American producers, don't use the "e." Other countries outside of these five big producers — America, Scotland, Ireland, Japan, and Canada — also almost always use the "whisky" spelling over "whiskey." (Side note: plural of whiskey is whiskeys; plural of whisky is whiskies.) In terms of why there are multiple spellings, that's all about the origin of the word, which is rooted in the Latin aqua vitae. Aqua vitae was the Latin term for distilled spirits, and was spread throughout Europe thanks to the Roman Empire. Aqua vitae was then translated into Irish Gaelic as uisce beatha and into Scottish Gaelic as uisge beatha. When those terms were anglicized they became whiskey and whisky respectively. Sound out uisce in your head the way you would intuitively to hear how it became whiskey.HOW WHISKEY IS MADE

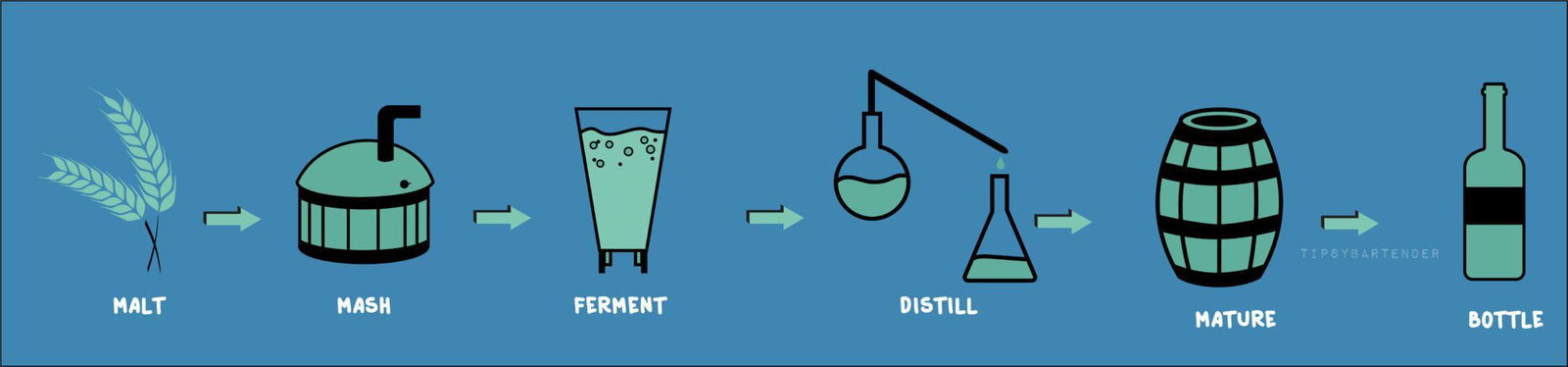

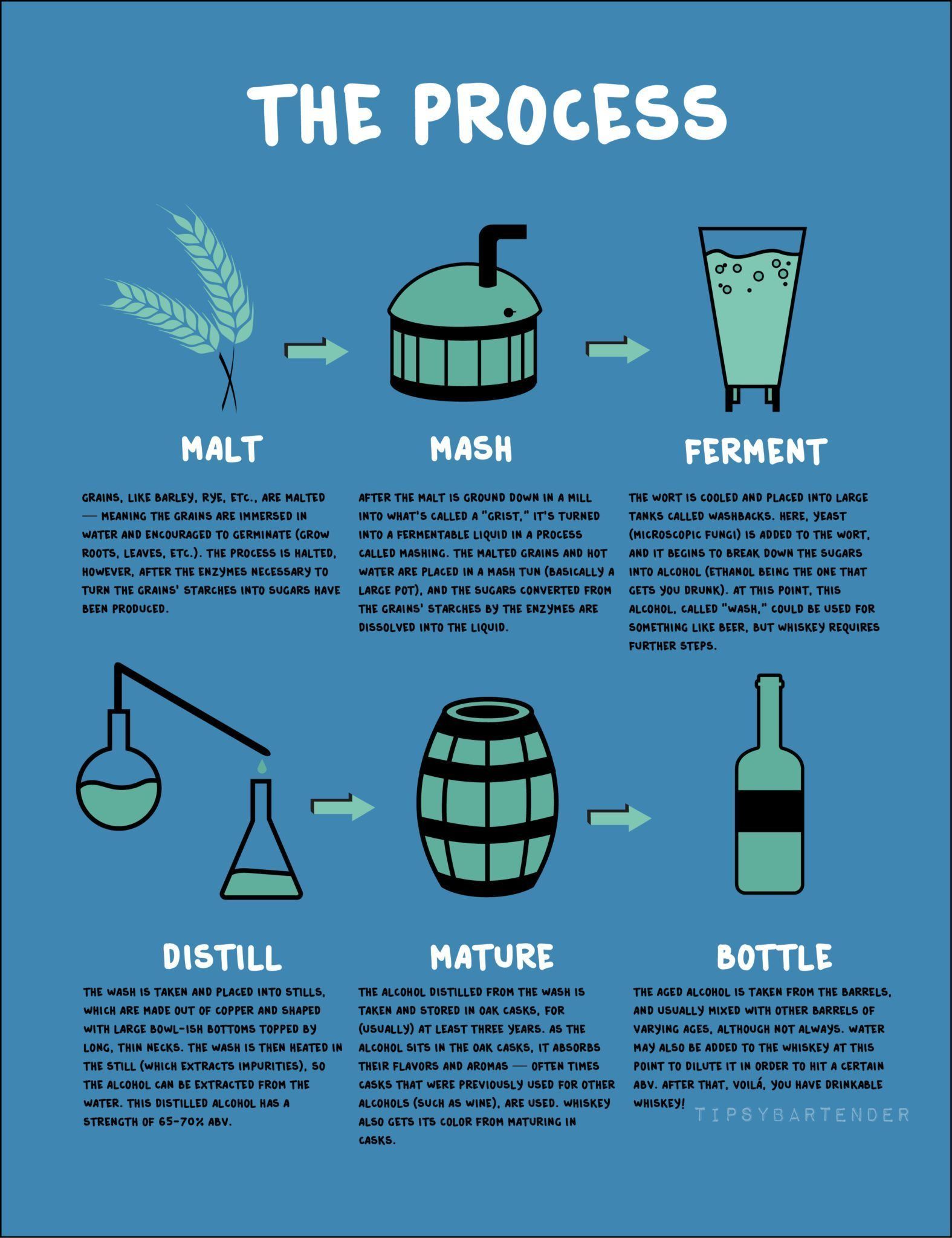

Now that we've got the name and history down, let's get into the nitty-gritty of how whiskey is made. And when it comes to the essential process, you're basically looking at the six following steps diagramed below.

1. Malting:

The first step in making whiskey is known as malting. This step is all about developing the enzymes (molecular catalysts), which will eventually turn the grain's starches into soluble sugars, which will in turn be converted into ethanol by the yeast added later. Basically what's happening during this step is the encouragement of grain seeds to germinate, or catalyze the process of becoming a plant. Producers want the seeds to germinate because during this process the enzymes required to turn the seeds' starches into soluble sugars (maltose) are created. If you want to go really deep into the science here, this page is perfect. https://giphy.com/embed/l378maSk3lsCDdvbi In order to induce germination, the grain is soaked in warm water for around two to three days, and then spread out on the floor of a malting house. In the malting house, the grain is regularly turned by dudes with shovels to maintain a consistent temperature — sometimes big turning barrel machines perform this function as well. Once the grain has released the enzymes necessary to turn its starches into soluble sugars, the germination process is halted with heat. Drying out the grain occurs in various ways: Many Scottish whisky makers use kilns powered by peat fires, for example, which can add a smoky flavor to the final product. (Peat is a bunch of partially decomposed plant matter.) Now that you've developed the enzymes required to turn the grain's starches into soluble sugars, and dried everything out, you have yourself some "malt." Inside the malting house. Above image: Wikimedia / Lakeworther

https://giphy.com/embed/1Zp3FIDcS4uH2EbZu1

Inside the malting house. Above image: Wikimedia / Lakeworther

https://giphy.com/embed/1Zp3FIDcS4uH2EbZu1

2. Mashing:

Once you've ground down your malt with a mill into what's called a "grist" — a bunch of dried, de-husked seeds that have germinated — you're ready to mash. In this step, the grist is mixed with warm water in giant insulated containers called mash tuns. Inside the mash tuns, the warm water encourages the enzymes in the grist to break down its starches into soluble sugars. These soluble sugars are also extracted from the seeds and pulled into the warm water, and the result is a sugary, non-alcoholic liquid known as "wort." The wort is then strained and drained out of the bottom of the mash tuns. (Side note: There are varied processes for mashing, e.g. decoction mashing, which takes a portion of the grains from the grist, boils them, and then returns them to said grist to raise the overall temperature inside the mash tun.) Inside a mash tun. Above image: Wikimedia / Ikiwaner

https://giphy.com/embed/35C96zcIqYLo6FkJip

Inside a mash tun. Above image: Wikimedia / Ikiwaner

https://giphy.com/embed/35C96zcIqYLo6FkJip

3. Fermentation:

Once you have the wort — the liquid infused with maltose sugar — you're ready for fermentation. This process begins by cooling the wort and passing into washback tanks, which are pictured below. At this point the yeast, which is a single-celled fungus, is added into the mix. The yeast begins to consume the soluble sugars and produce as byproducts ethanol and CO2. Although at this point, the ethanol-containing liquid, known as "the wash," is only a relatively paltry 5-10% ABV. To increase the ABV, the wash needs to be distilled. If you really want to get into more detail for the fermentation step, you can read about the multiple types of washbacks that distillers like to use — which are made of wood, stainless steel, etc. — as well as the varying types of yeast that can be used. But the most crucial point to understand here is that the yeast is turning the soluble sugars into ethanol. Above: View of washbacks. Image: Wikimedia / Avarim, Below: Yeast fermenting sugars, CO2 byproduct creating bubbles

https://giphy.com/embed/LWFfl28AspNqKMHrBS

Above: View of washbacks. Image: Wikimedia / Avarim, Below: Yeast fermenting sugars, CO2 byproduct creating bubbles

https://giphy.com/embed/LWFfl28AspNqKMHrBS

4. Distillation:

Now that you have the wash, a liquid that's 5-10% ABV, it's time to do some distillation to up that alcohol content. This process is somewhat complex, and varied, but the essential goal here is to increase ABV by getting rid of water. In order to concentrate the ABV of the wash, it's dumped inside of copper stills (pictured below), which basically act as giant kettles. The stills, which in the case of pot stills are kind of shaped like vuvuzelas with their necks bent, have their bulbous bottoms heated by some type of heating element (e.g. steam). The heat vaporizes the wash inside of the stills, but because different substances have different boiling points, the ethanol, which has a boiling point of 173.1 degrees Fahrenheit, is converted into vapor while the water, which has a boiling point of 212 degrees Fahrenheit, remains a liquid. Scotch whiskey stills. Image: Finlay McWalter

The distilled alcohol compounds fire up the inside of the still thanks to all that heat energy, hit the kink in the still's neck, move down the thinning tube — known as the lyne arm — that eventually runs, coiled, through a tank of cold water. The cold water condenses the alcohol vapor, turning it back into a liquid that's then re-collected.

Note that this process usually happens twice, with the wash first being heated, cooled and condensed in a wash still, and then again in a spirit still; the spirit still performs the same function, but heats up the higher ABV liquid collected from the wash still. (Side note: after the liquid is distilled the first time, it has an ABV of about 25-35% and is known as "low wines." After the low wines have been distilled again, even perhaps a third time in the case of many Irish whiskeys, the liquid has an average ABV of about 67.5% — although this percentage varies.)

https://giphy.com/embed/26osAtFnsLw3kvEeH9

Now, that's the essential process here, but as with everything related to whiskey, there's usually a lot more going on. For one, the reason the stills are made of copper, or at least lined with copper, is because copper removes sulfur-based compounds from the wash, which would negatively affect the taste of the final product — for example hydrogen sulfide, which is removed by the copper, would give the whiskey a rotten-egg aroma. Some of the other chemicals that would affect the whiskey's final flavor are also removed at this stage.

On top of all that, differently shaped stills are used for different types of whiskey in different countries, a fact discussed further in the Four Common Whiskey Types section.

Scotch whiskey stills. Image: Finlay McWalter

The distilled alcohol compounds fire up the inside of the still thanks to all that heat energy, hit the kink in the still's neck, move down the thinning tube — known as the lyne arm — that eventually runs, coiled, through a tank of cold water. The cold water condenses the alcohol vapor, turning it back into a liquid that's then re-collected.

Note that this process usually happens twice, with the wash first being heated, cooled and condensed in a wash still, and then again in a spirit still; the spirit still performs the same function, but heats up the higher ABV liquid collected from the wash still. (Side note: after the liquid is distilled the first time, it has an ABV of about 25-35% and is known as "low wines." After the low wines have been distilled again, even perhaps a third time in the case of many Irish whiskeys, the liquid has an average ABV of about 67.5% — although this percentage varies.)

https://giphy.com/embed/26osAtFnsLw3kvEeH9

Now, that's the essential process here, but as with everything related to whiskey, there's usually a lot more going on. For one, the reason the stills are made of copper, or at least lined with copper, is because copper removes sulfur-based compounds from the wash, which would negatively affect the taste of the final product — for example hydrogen sulfide, which is removed by the copper, would give the whiskey a rotten-egg aroma. Some of the other chemicals that would affect the whiskey's final flavor are also removed at this stage.

On top of all that, differently shaped stills are used for different types of whiskey in different countries, a fact discussed further in the Four Common Whiskey Types section.

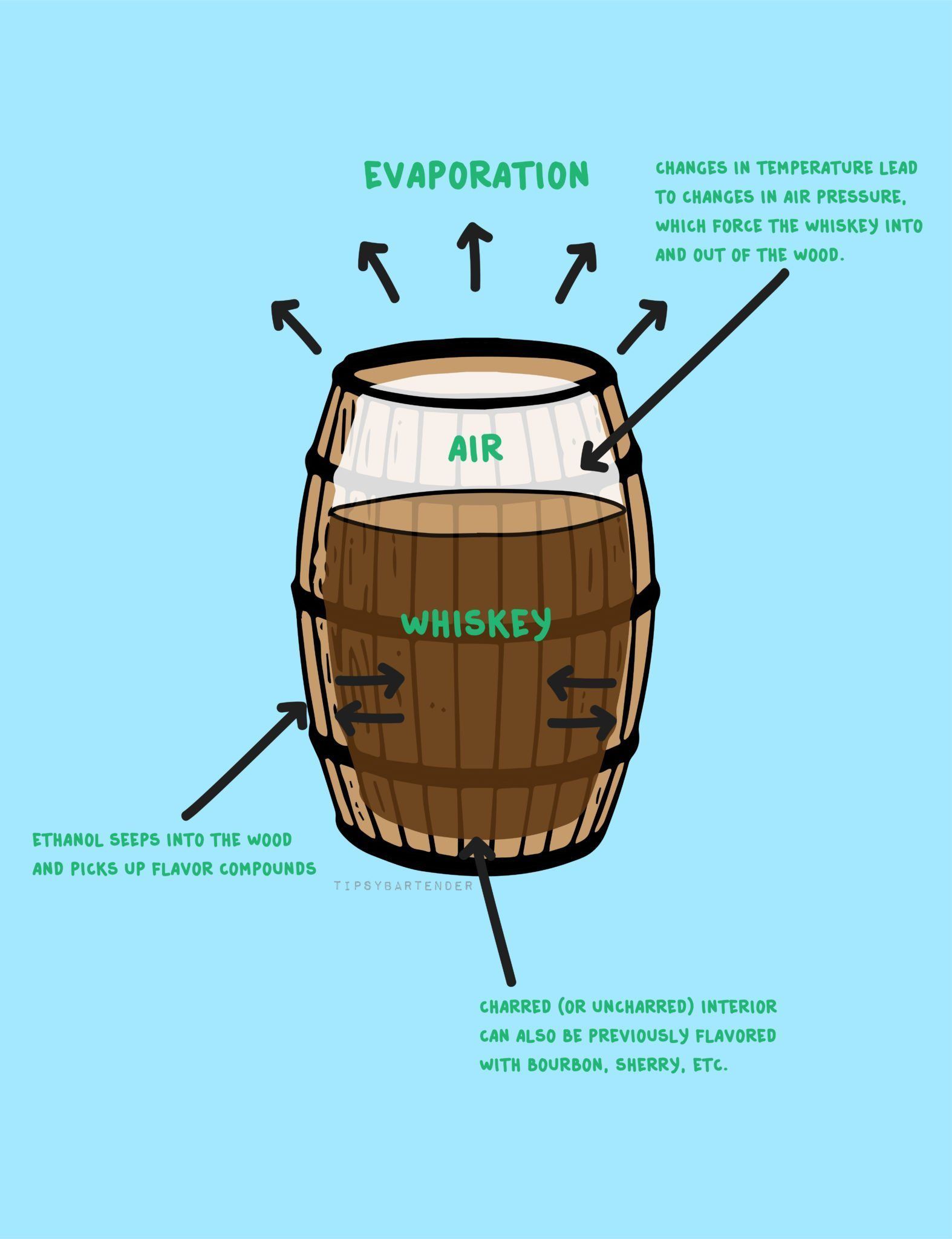

5. Aging

Finally, we get to where the majority (somewhere in the neighborhood of 60-80%) of whiskey's flavor, and nearly all of its color, comes from — barrel aging. Again, it seems like this is a very simple procedure that only consists of pouring the distilled grain alcohol into wood barrels and letting it sit there for a few years, or perhaps decades in some instances. But this is whiskey we're talking about, so even this step involves a crazy amount of hidden science and technique. Basically, as mentioned in the What Is Whiskey section above, the distilled ethanol is a solvent, so over time it's going to munch off various chemical compounds from the wood barrel, which will affect the whiskey's flavor and color. How this munching process takes place however, varies widely depending on the type of wood the barrel is made out of, if the barrel is charred, if the barrel has been used previously to store other alcohols, the climate of the region and warehouse in which the barrels are stored, and of course, how long the alcohol is stored in the barrels. Image of the insides of both charred and uncharred casks. Image: Flickr / rick

All of these factors will affect flavor and color, and almost all of them change depending on where in the world the whiskey is being made. For example, in the U.S., whiskey must be aged in a new charred oak barrel by law to be considered a patented Bourbon. In Scotland, many distilleries will use used Bourbon barrels from the U.S. to age their Scotch. The list of variations in method goes on and on depending on the region and particular whiskey-making organization.

As far as the essential flavor and coloring process, the alcohol is poured into the barrels with a typical cask strength of 60-65% ABV, and then it all boils down to five essential processes: extraction, evaporation, oxidation, filtration, and coloration.

https://giphy.com/embed/zLhIIGMYA9Dos

Extraction: Extraction is all about the whiskey seeping into and out of the wood barrels in order to grab flavor compounds. As temperatures change, so does pressure inside of the barrel. Warmer temperatures cause an increase in pressure, forcing the whiskey into the porous membrane of the wood, where it snatches flavor compounds such as vanillins (chemical compounds that provide vanilla flavoring) and tannins (chemical compounds that provide dry, sharp flavors similar to those of wine or black tea). When the temperature cools and pressure decreases, the whiskey drips back out of the wood, bringing along those flavor compounds. To imagine this process, you can think about the wood barrel expanding and contracting as it breathes the whiskey in and out.

(Side note: Because temperature affects pressure and pressure affects the rate at which flavor compounds are gathered by the whiskey, different climates will age whiskey at different rates. For example, whiskey often ages four times faster in Kentucky than it does in Scotland, as Kentucky's climate has much more severe swings from hot to cold.)

Evaporation: Because the wood that the casks are made of is porous, some of the alcohol inside the cask evaporates — this evaporated alcohol is known as The Angels' Share, and usually happens to the tune of about 2% every year. Which means if you barrel age a particular whiskey for 25 years, you could lose up to half the alcohol content. Note that water can and does also evaporate; higher humidity will cause more alcohol to evaporate, lower humidity will cause more water to evaporate.

Image of the insides of both charred and uncharred casks. Image: Flickr / rick

All of these factors will affect flavor and color, and almost all of them change depending on where in the world the whiskey is being made. For example, in the U.S., whiskey must be aged in a new charred oak barrel by law to be considered a patented Bourbon. In Scotland, many distilleries will use used Bourbon barrels from the U.S. to age their Scotch. The list of variations in method goes on and on depending on the region and particular whiskey-making organization.

As far as the essential flavor and coloring process, the alcohol is poured into the barrels with a typical cask strength of 60-65% ABV, and then it all boils down to five essential processes: extraction, evaporation, oxidation, filtration, and coloration.

https://giphy.com/embed/zLhIIGMYA9Dos

Extraction: Extraction is all about the whiskey seeping into and out of the wood barrels in order to grab flavor compounds. As temperatures change, so does pressure inside of the barrel. Warmer temperatures cause an increase in pressure, forcing the whiskey into the porous membrane of the wood, where it snatches flavor compounds such as vanillins (chemical compounds that provide vanilla flavoring) and tannins (chemical compounds that provide dry, sharp flavors similar to those of wine or black tea). When the temperature cools and pressure decreases, the whiskey drips back out of the wood, bringing along those flavor compounds. To imagine this process, you can think about the wood barrel expanding and contracting as it breathes the whiskey in and out.

(Side note: Because temperature affects pressure and pressure affects the rate at which flavor compounds are gathered by the whiskey, different climates will age whiskey at different rates. For example, whiskey often ages four times faster in Kentucky than it does in Scotland, as Kentucky's climate has much more severe swings from hot to cold.)

Evaporation: Because the wood that the casks are made of is porous, some of the alcohol inside the cask evaporates — this evaporated alcohol is known as The Angels' Share, and usually happens to the tune of about 2% every year. Which means if you barrel age a particular whiskey for 25 years, you could lose up to half the alcohol content. Note that water can and does also evaporate; higher humidity will cause more alcohol to evaporate, lower humidity will cause more water to evaporate.

Oxidation: Oxidation is another process that occurs during the barrel aging process, which also has an effect on the final product's flavor profile. Because the porous barrels have permeable membranes, they allow in small amounts of oxygen, which in turn react chemically with some of the compounds in the whiskey. These chemical reactions lead to the proliferation of flavor compounds, especially a group of compounds called esters, which are created during fermentation and responsible for flavors that tend to be fruity, creamy, and floral.

Filtration: In terms of filtration, we're again talking about the way the whiskey is breathed in and out of the barrel. Because many of the barrels holding the whiskey have been burned with a flame in some fashion — e.g. charred or toasted — the wood effectively becomes a big ol' carbon filter. As the whiskey passes into and out of the wood, that carbon filter, which works much in the same way as your water filter at home does, smooths out the whiskey and removes more unwanted chemical compounds.

Coloration: Just as the whiskey picks up flavor compounds from the wood, it also picks up chemical compounds that affect the whiskey's color. The coloring that's picked up is again dependent on the type of barrels used — Bourbons will usually develop darker colors than Scotches aged in barrels previously used for aging Bourbons, for example, as the barrels used the second time around for the Scotches have already lost a portion of their color-affecting compounds to the first round of Bourbons.

Whiskey, unlike wine, does not age in the bottle. At all. Whiskey only ages in the barrel. So if a whiskey that spent 25 years in the barrel was bottled in say, 1970, you don't have a whiskey that's now 73 years old (as of 2018) — the whiskey is still only 25 years old.

Oxidation: Oxidation is another process that occurs during the barrel aging process, which also has an effect on the final product's flavor profile. Because the porous barrels have permeable membranes, they allow in small amounts of oxygen, which in turn react chemically with some of the compounds in the whiskey. These chemical reactions lead to the proliferation of flavor compounds, especially a group of compounds called esters, which are created during fermentation and responsible for flavors that tend to be fruity, creamy, and floral.

Filtration: In terms of filtration, we're again talking about the way the whiskey is breathed in and out of the barrel. Because many of the barrels holding the whiskey have been burned with a flame in some fashion — e.g. charred or toasted — the wood effectively becomes a big ol' carbon filter. As the whiskey passes into and out of the wood, that carbon filter, which works much in the same way as your water filter at home does, smooths out the whiskey and removes more unwanted chemical compounds.

Coloration: Just as the whiskey picks up flavor compounds from the wood, it also picks up chemical compounds that affect the whiskey's color. The coloring that's picked up is again dependent on the type of barrels used — Bourbons will usually develop darker colors than Scotches aged in barrels previously used for aging Bourbons, for example, as the barrels used the second time around for the Scotches have already lost a portion of their color-affecting compounds to the first round of Bourbons.

Whiskey, unlike wine, does not age in the bottle. At all. Whiskey only ages in the barrel. So if a whiskey that spent 25 years in the barrel was bottled in say, 1970, you don't have a whiskey that's now 73 years old (as of 2018) — the whiskey is still only 25 years old.

Wooden cask used for aging whiskey. Image: Yves Cosentino

Wooden cask used for aging whiskey. Image: Yves Cosentino

6. Bottling

Finally! Now we're so close to having our finished whiskey product you can taste it — literally, if you have a thief. And relative to the other steps, this one is actually pretty simple. Here, distillers pour the whiskey — which is at least 40% ABV by law in most prominent whiskey-making countries — out of the barrels, through a filter (in order to get rid of any barrel hunks that may have chunked off during aging) and then cut it with filtered water in order to bring down the ABV from somewhere in the neighborhood of 68-72% ABV to closer to 40% ABV. Not all whiskeys are diluted with water before being bottled however; some "cask strength" whiskeys are taken straight from the cask after filtration and bottled, giving consumers a chance to taste the whisky in its most natural, undiluted state. https://giphy.com/embed/l0HlVGqZZj48Chv0I (Side note: There is also an optional step that's called Chill Filtration. Chill filtration is a process by which the whiskey is taken from the barrel, cooled down to very cold temperatures, around 0 to -4 degrees Celsius, and then passed through metal mesh or paper filters. The reason the whiskey is chilled is because the cold temperature hardens impurities such as fatty acids and proteins so that they can be strained out by the filters. This process is done for purely cosmetic reasons, so that when a whiskey is chilled with ice in the glass, it does not get cloudy.) Bottling Bourbon whiskey. Image: Flickr / Paul Joseph

Bottling Bourbon whiskey. Image: Flickr / Paul Joseph

WHISKEY NOMENCLATURE

Whiskey names sound fancy as hell, right? Like a bunch of words — single malt, blended, grain, scotch, bourbon, single barrel, straight, etc. — that somebody would say if they were trying really hard to show off their whiskey knowledge... hey, let's learn those terms so we can do just that! Whiskey names vary quite a bit, with two main components needing some explanation, a third that doesn't really need explanation, and a few other frequently used terms:

Whiskey names vary quite a bit, with two main components needing some explanation, a third that doesn't really need explanation, and a few other frequently used terms:

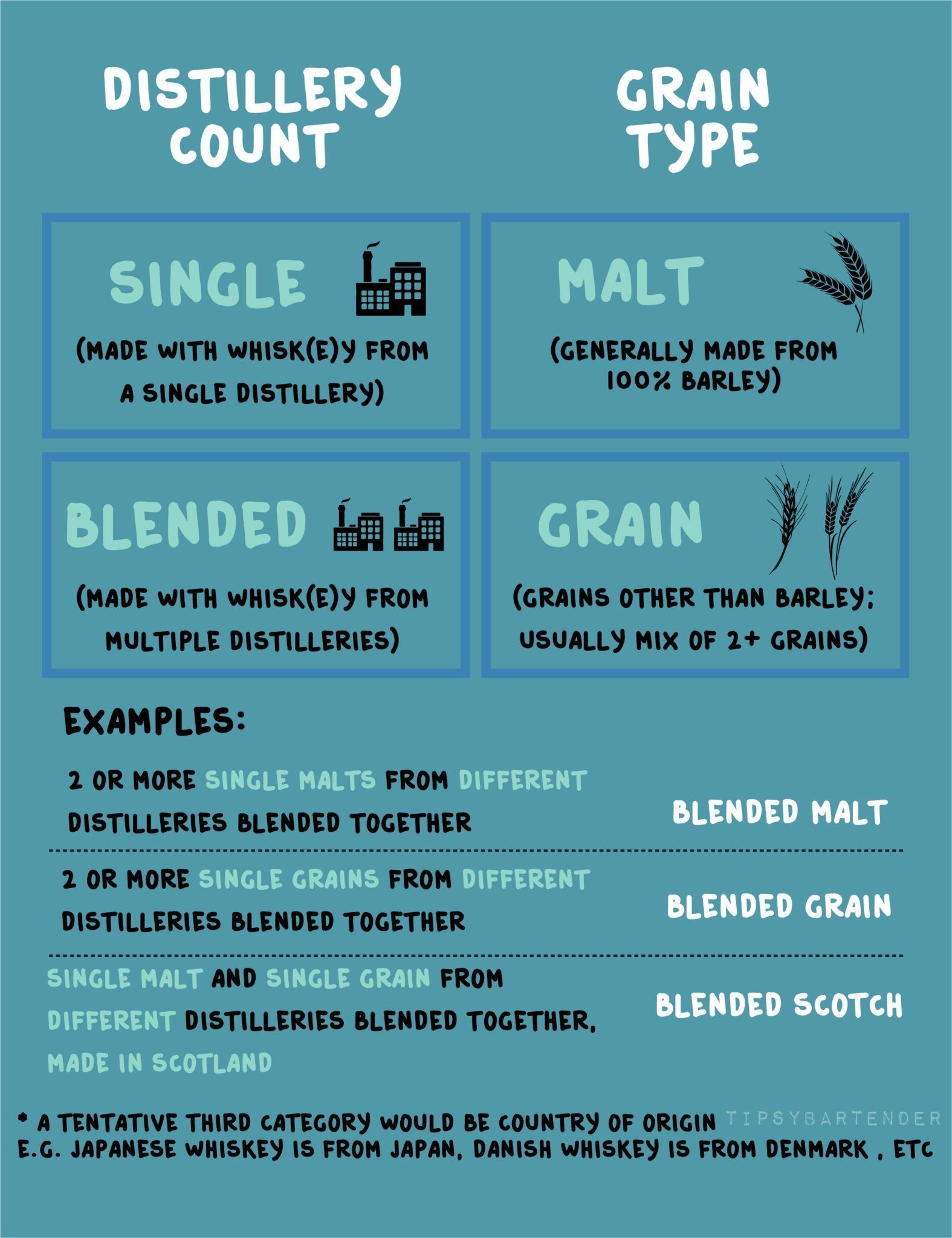

NAME COMPONENT PART ONE: HOW MANY DISTILLERIES, YO?

The first part of many whiskeys' names has to do with how many distilleries donated the booze DNA to a given whiskey baby. So for example, if you have a Single Malt Scotch, that single denotes that a single distillery filled up that bottle with whiskey. If you have a Blended Malt Scotch, or a Blended Irish Whiskey for that matter — any whiskey with "Blended" in its name — then the whiskey in the bottle came from two or more distilleries.NAME COMPONENT PART TWO: WHAT KINDA GRAINS, BRO?

Now we look at that second part of the name, which often says either "Malt" or "Grain," and is referring to the type or types of grains used — e.g. rye, corn, barley, wheat, etc. If the label says Malt, that means the whiskey is made from a fermented mash that's primarily made of malted barley, or entirely made of malted barely. So if you see malt, think either majority barley, or entirely barley as the whiskey's grain ingredient. (Note that a Scotch with Malt in its name must be made exclusively of barley according to Scotch regulations passed in 2009 in Scotland.) https://giphy.com/embed/iee67fNy17JyHUN7MK Grain whiskey refers to whiskey made, at least in some portion, from grains other than barley. So if you see the word Grain on a bottle of whiskey, keep in mind that it's either a mix of barley and other grains, or entirely made of other types of grains aside from barley.NAME COMPONENT PART THREE: WHERE'S IT FROM?

This part doesn't need any explanation, but you'll see it on tons of labels — where the whiskey was made. Japanese whisky is made in Japan, Canadian whisky is made in Canada, etc. You get the idea.FREQUENT TERMS YOU'LL SEE ON LABELS:

SCOTCH Scotch is only from Scotland. If it says Scotch, it's from Scotland. BOURBON Whiskey that is a "distinctive product of the United States." If it says Bourbon, it was made in the U.S. Bourbons are at least 51% corn by law. (Further Bourbon details are given in the Common Whiskey Types section below.) STRAIGHT WHISKEY If you see "Straight" on a Bourbon's label, that means the whiskey in the bottle does not exceed 80% ABV, has been aged for at least two years in charred new oak barrels (except for corn whiskey, which must be aged in uncharred or used oak barrels), and entered the cask at an ABV not exceeding 62.5%. SINGLE BARREL A whiskey that's been taken and bottled from a single barrel — note that this different from taken from a single distillery — and not mixed with any other whiskeys. Various whiskeys. Image: Flickr / Zach Marzouk

BOTTLED IN BOND

Bottled in bond is a term that's only applied to whiskeys made in the U.S. In order for a bottle of whiskey to be labeled as Bottled in Bond (or bonded), it must have: been distilled in a single season by one distiller at one distillery, aged in a federally bonded warehouse under government supervision for a minimum of four years, and bottled at 50% ABV. A bottled-in-bond whiskey's label must also display the name of the distillery where the whiskey was distilled, as well as where it was bottled if that happened at a different location.

CASK STRENGTH/BARREL PROOF

If you see "Cask Strength" or "Barrel Proof" on the bottle, that means that you're getting a completely undiluted (no water added) whiskey from the cask. So if you see either of these terms on your whiskey, expect a significantly higher ABV than normal.

https://giphy.com/embed/KRuSnyQJzBu0w

Small Batch, a term almost, although not entirely exclusive to American whiskeys, just means that the whiskey was mixed from a relatively small number of barrels. This label is a bit nebulous however, as there is no strict government regulation regarding how many barrels must be used to qualify a whiskey as "Small Batch."

SOUR MASH

Sour Mash is a term you'll see on Bourbon labels, and simply means that the whiskey producer used some amount of "spent mash" (previously fermented mash) in the new mash used for the Bourbon in the bottle you're holding. (This is done to affect flavor and PH balance.)

NON-CHILL FILTERED

This just means no chill filter process — which is explained above in the Bottling section — was applied to the whiskey. This is noted because chill filtration can sometimes be seen as negatively affecting the taste of the whiskey.

CARAMEL COLORING

Exactly what it sounds like — caramel coloring added.

Various whiskeys. Image: Flickr / Zach Marzouk

BOTTLED IN BOND

Bottled in bond is a term that's only applied to whiskeys made in the U.S. In order for a bottle of whiskey to be labeled as Bottled in Bond (or bonded), it must have: been distilled in a single season by one distiller at one distillery, aged in a federally bonded warehouse under government supervision for a minimum of four years, and bottled at 50% ABV. A bottled-in-bond whiskey's label must also display the name of the distillery where the whiskey was distilled, as well as where it was bottled if that happened at a different location.

CASK STRENGTH/BARREL PROOF

If you see "Cask Strength" or "Barrel Proof" on the bottle, that means that you're getting a completely undiluted (no water added) whiskey from the cask. So if you see either of these terms on your whiskey, expect a significantly higher ABV than normal.

https://giphy.com/embed/KRuSnyQJzBu0w

Small Batch, a term almost, although not entirely exclusive to American whiskeys, just means that the whiskey was mixed from a relatively small number of barrels. This label is a bit nebulous however, as there is no strict government regulation regarding how many barrels must be used to qualify a whiskey as "Small Batch."

SOUR MASH

Sour Mash is a term you'll see on Bourbon labels, and simply means that the whiskey producer used some amount of "spent mash" (previously fermented mash) in the new mash used for the Bourbon in the bottle you're holding. (This is done to affect flavor and PH balance.)

NON-CHILL FILTERED

This just means no chill filter process — which is explained above in the Bottling section — was applied to the whiskey. This is noted because chill filtration can sometimes be seen as negatively affecting the taste of the whiskey.

CARAMEL COLORING

Exactly what it sounds like — caramel coloring added.

COMMON WHISKEY TYPES

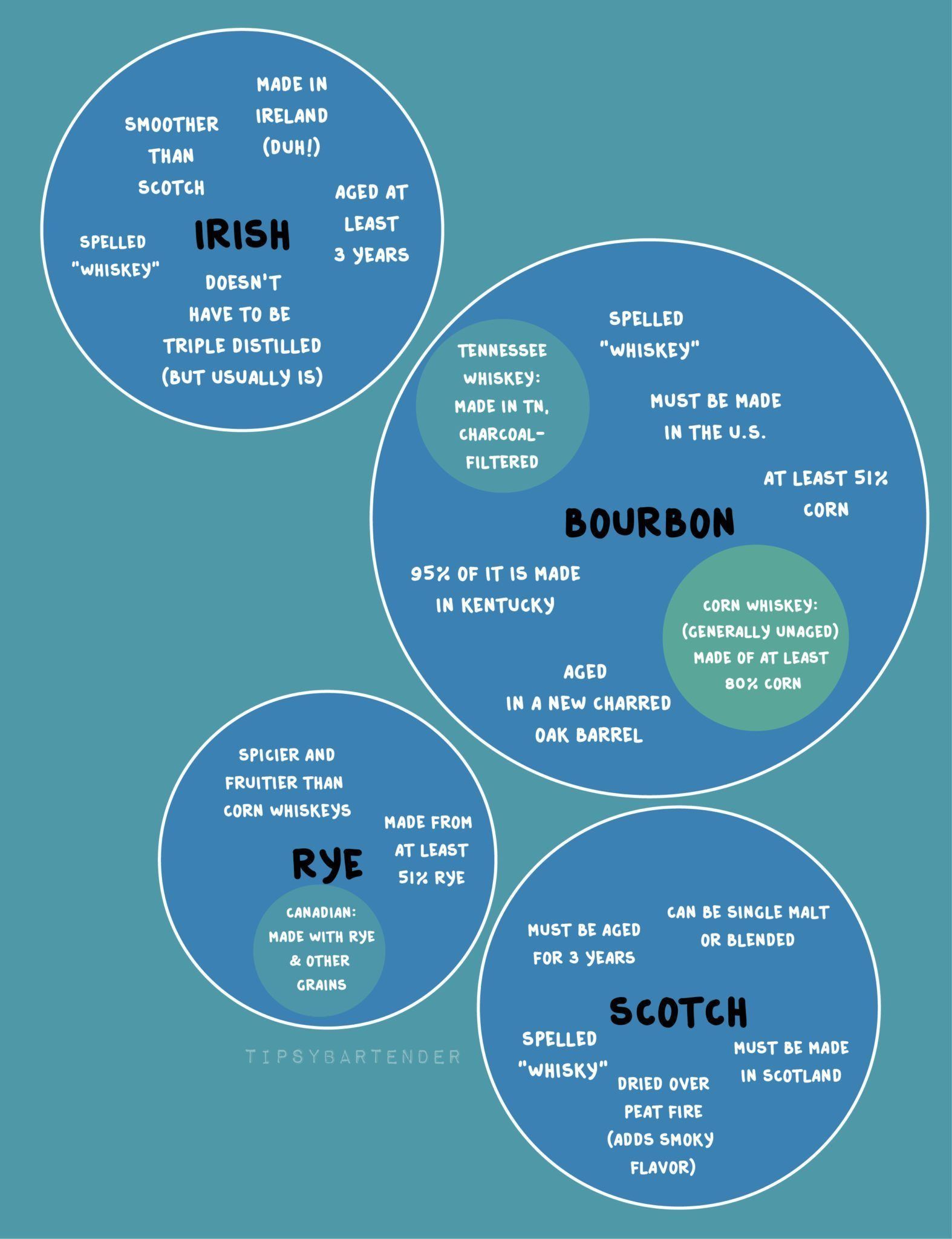

Now let's get an overview of some of the most popular whiskey types, briefly breaking down the processes and regulations that are required for each category. SCOTCH WHISKY (NO "E"!)

Scotch is malt or grain whisky made in Scotland. By law, Scotch must be aged in oak barrels for at least three years, and must also meet several other requirements regarding the distillation process. Remember that if you see "Malt" on a Scotch label, that means, by law, that it's made from 100% barley. The age on the bottle denotes the youngest whisky in the bottle.

https://giphy.com/embed/B8Bp8MfpmKbWU

Single Malt Scotch = 100% barley whisky from a single distillery

Blended Malt Scotch = 100% barley whisky from multiple distilleries

Single Grain Scotch = Mixed grain whisky from a single distillery

Blended Grain Scotch = Mixed grain whisky from multiple distilleries

Some of the most popular Scotch brands are: Johnnie Walker, Ballantine's, Chivas Regal, Dewar's, and Label 5.

BOURBON WHISKEY (WITH AN "E")

Bourbon is made, by law, only in the U.S., made from at least 51% malted corn, distilled at no higher than 80% ABV, aged in new charred oak barrels, and barreled at 125 proof (62.5% ABV). Keep in mind that to make a Bourbon, there is no aging requirement. (Below is a brief GIF showing how the barrels used for aging Bourbons are charred.)

Some of the most popular Bourbon brands are: Blanton's, Woodford Reserve, Jim Beam, Maker's Mark, and Wild Turkey

https://giphy.com/embed/3ohrymAsBCZxZaDdpS

RYE WHISKEY ("E" IN U.S., NO "E" IN CANADA)

According to U.S. law, rye whiskey must be made from a mash that's at least 51% rye, distilled to no more than 80% ABV, and aged in new charred oak barrels in the U.S. with an initial cask strength no greater than 62.5% ABV. Rye whiskey that's been aged in this fashion in the U.S. for at least two years and not blended with any other whiskeys can be legally labeled "Straight Rye Whiskey."

For Canada's version of rye whisky (no "e" up north), see below.

Some of the most popular rye whiskeys are: WhistlePig, Bulleit Rye, Redemption Rye, and Knob Creek

CANADIAN WHISKY (NO "E"!)

Canadian whisky is generally considered to be a rye whisky, although that's a bit of a misnomer, as Canadian whisky mash bills — the makeup of the grains used to make the whisky— don't need to be made up of 51% rye, or any rye at all. In fact, they're often made with a large percentage of corn mash. Why are Canadian whisky and Rye whisky used interchangeably in Canada then? Because when whisky makers first added flavorful rye to their mashes, it became popular amongst consumers, and now many Canadian whiskies are at least flavored with rye.

Also, by law, Canadian whisky must be aged in wood barrels in Canada for at least three years, and the finished product must be at least 40% ABV.

Some of the most popular Canadian whiskies are: Lot 40 Canadian Rye Whisky, Stalk and Barrel, Danfield's, Pike Creek, Collingwood, and WhistlePig

TENNESSEE WHISKEY (BOTH SPELLING VARIATIONS OCCUR)

Tennessee whiskey meets all of the requirements of a Bourbon, but in order to qualify as a Tennessee whiskey, it must meet two additional criteria: It has to be made in Tennessee, and it has to undergo The Lincoln County Process. The Lincoln County Process is simply an additional filtration step for the whiskey before it's placed in the casks, where it's steeped over or passed through charcoal chips in order to remove impurities.

SCOTCH WHISKY (NO "E"!)

Scotch is malt or grain whisky made in Scotland. By law, Scotch must be aged in oak barrels for at least three years, and must also meet several other requirements regarding the distillation process. Remember that if you see "Malt" on a Scotch label, that means, by law, that it's made from 100% barley. The age on the bottle denotes the youngest whisky in the bottle.

https://giphy.com/embed/B8Bp8MfpmKbWU

Single Malt Scotch = 100% barley whisky from a single distillery

Blended Malt Scotch = 100% barley whisky from multiple distilleries

Single Grain Scotch = Mixed grain whisky from a single distillery

Blended Grain Scotch = Mixed grain whisky from multiple distilleries

Some of the most popular Scotch brands are: Johnnie Walker, Ballantine's, Chivas Regal, Dewar's, and Label 5.

BOURBON WHISKEY (WITH AN "E")

Bourbon is made, by law, only in the U.S., made from at least 51% malted corn, distilled at no higher than 80% ABV, aged in new charred oak barrels, and barreled at 125 proof (62.5% ABV). Keep in mind that to make a Bourbon, there is no aging requirement. (Below is a brief GIF showing how the barrels used for aging Bourbons are charred.)

Some of the most popular Bourbon brands are: Blanton's, Woodford Reserve, Jim Beam, Maker's Mark, and Wild Turkey

https://giphy.com/embed/3ohrymAsBCZxZaDdpS

RYE WHISKEY ("E" IN U.S., NO "E" IN CANADA)

According to U.S. law, rye whiskey must be made from a mash that's at least 51% rye, distilled to no more than 80% ABV, and aged in new charred oak barrels in the U.S. with an initial cask strength no greater than 62.5% ABV. Rye whiskey that's been aged in this fashion in the U.S. for at least two years and not blended with any other whiskeys can be legally labeled "Straight Rye Whiskey."

For Canada's version of rye whisky (no "e" up north), see below.

Some of the most popular rye whiskeys are: WhistlePig, Bulleit Rye, Redemption Rye, and Knob Creek

CANADIAN WHISKY (NO "E"!)

Canadian whisky is generally considered to be a rye whisky, although that's a bit of a misnomer, as Canadian whisky mash bills — the makeup of the grains used to make the whisky— don't need to be made up of 51% rye, or any rye at all. In fact, they're often made with a large percentage of corn mash. Why are Canadian whisky and Rye whisky used interchangeably in Canada then? Because when whisky makers first added flavorful rye to their mashes, it became popular amongst consumers, and now many Canadian whiskies are at least flavored with rye.

Also, by law, Canadian whisky must be aged in wood barrels in Canada for at least three years, and the finished product must be at least 40% ABV.

Some of the most popular Canadian whiskies are: Lot 40 Canadian Rye Whisky, Stalk and Barrel, Danfield's, Pike Creek, Collingwood, and WhistlePig

TENNESSEE WHISKEY (BOTH SPELLING VARIATIONS OCCUR)

Tennessee whiskey meets all of the requirements of a Bourbon, but in order to qualify as a Tennessee whiskey, it must meet two additional criteria: It has to be made in Tennessee, and it has to undergo The Lincoln County Process. The Lincoln County Process is simply an additional filtration step for the whiskey before it's placed in the casks, where it's steeped over or passed through charcoal chips in order to remove impurities.

Wood being burned in order to make the charcoal that will be used for The Lincoln County process. Image: Flickr / twinfountain

Some of the most popular Tennessee whiskeys are: Jack Daniel's, George Dickel, and Benjamin Prichard's (* Prichard being the one Tennessee whiskey maker that doesn't currently use The Lincoln County Process.)

CORN WHISKEY (A.K.A. WHITE LIGHTNING OR MOONSHINE)

Corn whiskey is made in America, made from a mash of at least 80% corn, and distilled to a maximum ABV of 80%. If corn whiskey is aged — it has no aging restrictions — it must be in uncharred or previously used oak barrels. It also has to be pumped into the barrel at a max ABV of 62.5%. Corn whiskey is usually only aged for six months or less, although straight corn whiskey is aged in new uncharred oak barrels for two years or more.

Some of the most popular corn whiskeys are: Firefly Moonshine, Midnight Moon, and Balcones

IRISH WHISKEY (WITH AN "E")

Irish whiskey is usually triple distilled — although it doesn't need to be — and must, by law, be made in Ireland (obviously), have an ABV of at least 40%, be aged in wooden casks for at least three years, and have its coloring adjusted with either water or caramel coloring only.

https://giphy.com/embed/xReGW7oRLOM8g

SINGLE POT STILL WHISKEY

Single pot still whiskey is a type of Irish whiskey — made in Ireland only! — that's made from a mash of malted and unmalted barley distilled in a pot still (sometimes small amounts of raw oats and wheat are also added). The unmalted barley tends to give this type of whiskey a spicier flavor and thicker texture than normal single malt whiskeys.

Some of the most popular single pot still whiskeys are: Midleton Barry Crocket Legacy, Green Spot, Yellow Spot, and Red Breast

Wood being burned in order to make the charcoal that will be used for The Lincoln County process. Image: Flickr / twinfountain

Some of the most popular Tennessee whiskeys are: Jack Daniel's, George Dickel, and Benjamin Prichard's (* Prichard being the one Tennessee whiskey maker that doesn't currently use The Lincoln County Process.)

CORN WHISKEY (A.K.A. WHITE LIGHTNING OR MOONSHINE)

Corn whiskey is made in America, made from a mash of at least 80% corn, and distilled to a maximum ABV of 80%. If corn whiskey is aged — it has no aging restrictions — it must be in uncharred or previously used oak barrels. It also has to be pumped into the barrel at a max ABV of 62.5%. Corn whiskey is usually only aged for six months or less, although straight corn whiskey is aged in new uncharred oak barrels for two years or more.

Some of the most popular corn whiskeys are: Firefly Moonshine, Midnight Moon, and Balcones

IRISH WHISKEY (WITH AN "E")

Irish whiskey is usually triple distilled — although it doesn't need to be — and must, by law, be made in Ireland (obviously), have an ABV of at least 40%, be aged in wooden casks for at least three years, and have its coloring adjusted with either water or caramel coloring only.

https://giphy.com/embed/xReGW7oRLOM8g

SINGLE POT STILL WHISKEY

Single pot still whiskey is a type of Irish whiskey — made in Ireland only! — that's made from a mash of malted and unmalted barley distilled in a pot still (sometimes small amounts of raw oats and wheat are also added). The unmalted barley tends to give this type of whiskey a spicier flavor and thicker texture than normal single malt whiskeys.

Some of the most popular single pot still whiskeys are: Midleton Barry Crocket Legacy, Green Spot, Yellow Spot, and Red Breast

WHISKEY FLAVORS

(VERY) GENERAL FLAVOR PROFILES OF DIFFERENT WHISKEY TYPES

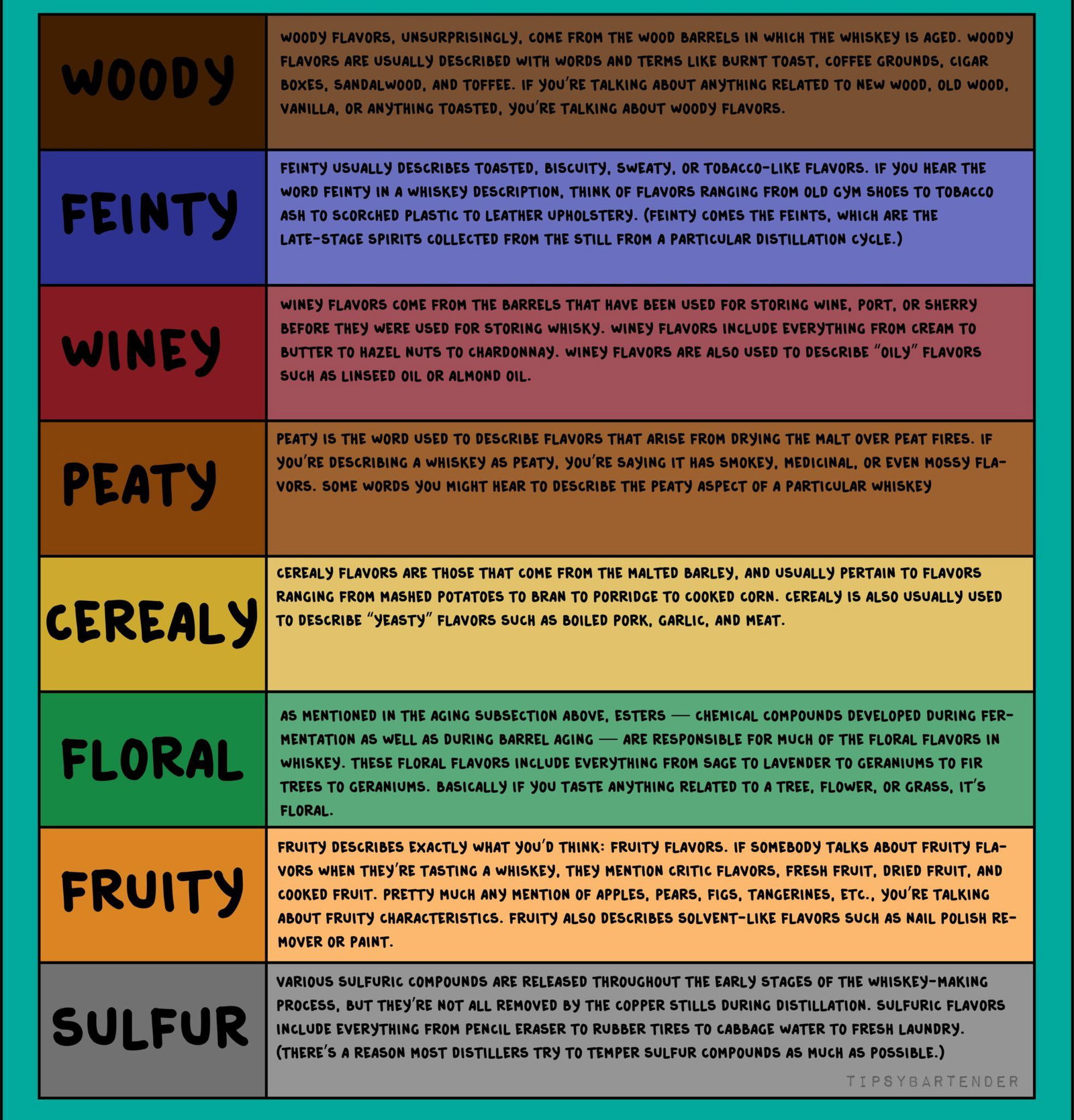

RYE WHISKEY In general, the higher the rye content of a whiskey, the spicier its flavoring is. Rye whiskeys tend to have less sweetness and more peppery flavoring, and are also bready (i.e. tastes like rye bread) and earthy, with hints of dry herbs. Grass notes and fruity aromas are also often present. TENNESSEE WHISKEY Tennessee whiskey is corn-based like Bourbons, so it shares many similar flavors, including many sweet tones of vanilla, sugar, honey, maple syrup, and caramel. Because Tennessee whiskey is required to undergo charcoal filtration via The Lincoln County Process, however, subtler flavors tend to emerge as well, like licorice. That charcoal filtering also tends to create a softer, drier, profile. SINGLE POT STILL WHISKEY Single pot still whiskeys — which are, again, only made in Ireland — tend to have spicier flavors, and even cereal flavors that have been described as "funky" thanks to their inclusion of unmalted barley. Single pot still whiskeys also tend to have tones of apricot, peaches, tropical fruits, and cocoa, and they often have a leathery finish. BOURBON WHISKEY Thanks to their being aged in new charred oak barrels, Bourbons tend to have flavors such as vanilla, honey, and caramel, as well as woody, nutty tones. You also get lots of floral aromas (especially citrus), as well as hints of vanilla, caramel, and even chocolate. https://giphy.com/embed/9rtpg8WmlpYad8kVdX CORN WHISKEY Corn whiskey tends to have a sweeter flavor, which leans toward vanilla and even maple syrup. Because corn whiskey is generally unaged, or aged in used barrels, you can taste much more of the corn-related flavors, as there are much fewer flavors coming from the barrel, or none at all. If a corn whiskey is aged in a barrel for a significant period of time, as with straight corn whiskeys (which are aged for two years), then you obviously get more barrel flavoring. MALT (BARLEY) WHISKEY Although whiskeys made from barley (malt whiskeys) have a very extensive range of flavor profiles, they often have sweeter flavors with hints of brown sugar and caramel. They also tend to have roasted and toffee-like cereal flavors. WHEAT WHISKEY Wheat whiskeys tend to have more cereal, earthy notes, with slightly sweet brown bread tones. They also tend to have gentler aromas with grassy notes, which have been described as smelling of the outdoors.HOW TO DESCRIBE WHISKEY FLAVORS

Note that many of these terms are umbrella terms for tons of subtle flavors, which can be explored further in this awesome little graph from whiskygals.ch. Although there is a metric ass-load of terms to describe whiskey flavors, what seems to be useful is going by the eight main categories outlined by the Pentlands Wheel, which was the first systematic attempt to categorize whiskey flavors undertaken by a group of scientists in Edinburgh, Scotland in the '70s.

WHISKEY BEST PRACTICES: HOW TO SNOB IT UP

OK, now that we have all of our whiskey knowledge down, it's time to have some fun and taste some damn whiskey already. But wait! You can't just pound the whiskey or use is it as an ingredient in a crazy-ass whiskey cocktail. Well, you can, of course, but not if you want to truly enjoy the whiskey like a connoisseur (read: snob). While there are many rules floating around the internet regarding how to drink your whiskey, we like the idea of following the rules laid out by Scotland-based Master Distiller Richard "The Nose" Paterson. Paterson began tasting whiskey when he was just eight years-old, and his nose is even insured for $2.5 million. And while the following guidelines aren't exact transcriptions of Paterson's style, he still is, we think reasonably, our biggest influence when it comes to whiskey tasting. THE GLASS First of all, let's talk about the glass you should use while snobbin' like a pro. And yes, only glassware is acceptable here — no drinking out of a coffee mug or 7-Eleven Big Gulp cup. If you really want get the best shot at properly tasting a whiskey, you'll want to go with a tulip-shaped glass (a.k.a. a copita-style glass or dock glass) that has a base on which to hold — a glass like the Glencairn whisky glass shown below, for example. Drinking whiskey out of a tulip-shaped glass with a base is good for multiple reasons: First of all, that concave closing means that more of the whiskey aromas are trapped in the glass: Because whiskey is constantly evaporating into the air, a glass with a wider opening that doesn't taper inward at the top will let out more aromas, which won't have a chance to hit your nose. Glencairn whisky glass. Image: Wikipedia / Amiko82

Second of all, a glass like the Glencairn whisky glass allows you to keep your damn hand away from the whiskey. If you hold the whiskey glass by the bottom of the glass instead of the base, you'll warm up the whiskey, thusly changing its flavor profile. You'll also want to be looking at your whiskey, and you can't do that if your hand is blocking it. So remember, pick a glass that will let you keep the aromas in, and keep your hand out of the picture.

There are, of course, a bunch of other acceptable glasses you can go with, including: the whiskey tumbler (good for whiskey on the rocks and cocktails, shown in the GIF below), the highball glass (allows for plenty of ice and mixer, is preferred in Japan), the snifter (makes you look fancy, but releases a lot of ethanol evaporation due to that wide mouth), and the NEAT whisky glass (a new type of glass that was made by accident at a glass-blowing factory, which happens to direct ethanol vapors away from the nose).

https://giphy.com/embed/mqd2sQsR5fuq4

ON THE ROCKS OR NEAT?

According to Paterson, you basically want to avoid ice in your glass like it's the plague. It chills down the whiskey too much and also dilutes it, subsequently muting some of the flavors. But, if you're willing to defy The Nose, try to keep the ice to a minimum, with just a few blocks. Also aim for blocks that have a relatively small surface area, as that will dilute your whiskey more slowly, but chill it at the same rate as blocks with larger surface areas.

DRINK IT IN WITH YOUR EYES

OK, now that you have your whiskey in your glass, it's time to swirl it around and take a good look at its colors and the way it adheres to the glass. In terms of the color, what you're basically trying to look for are signs regarding the whiskey's aging process.

https://giphy.com/embed/4EF4waRc1Ejth4Iq0V

In general, you'll see whiskeys take on darker colors the longer they've spent in the barrel. This isn't necessarily true in all cases, however, because the barrels vary. For example, Bourbons will take on a darker color over a shorter period of time relative to Scotches because they're being aged in new charred oak barrels that can give away a lot more pigment-affecting compounds. If you're a real expert, you may even be able to determine if caramel coloring has been added. (Also keep in mind that with a whiskey that hasn't undergone any aging, such as some corn whiskeys, you may not see any coloration at all.)

The legs (or tears) of the whiskey — the whiskey that runs down the inside of the glass after you've swirled it — aren't too important for judging quality, but they can tell you a little about the whiskey's texture. If the whiskey has short, slow-moving legs, it'll probably have a thicker texture in the mouth. If it has thinner legs that move relatively fast, that could imply less texture.

ADDING WATER

When you order your whiskey, you'll also want to order a glass or pitcher of distilled water — or even a bottle of water. Why? Because diluting your glass of whiskey just a bit with the right kind of water will drop the ABV, and more importantly, help to bring out all of the flavors. If you have two fingers' worth of whiskey in your glass, try pouring in a couple of thimblefuls of water. Paterson says you want an ABV of about 35% for perfect tasting, although it's hard to say exactly how'd you know that if you're just chilling in a bar with your amigos.

https://giphy.com/embed/oz5mzqTUo4xQtWtXDv

NOSING THE WHISKEY

Now it's time to stick your nose in your glass — and according to Paterson, that means really sticking your nose in there. You want to be very cautious with this step however, as when you stick your nose in a glass of whiskey and take a deep breath, you're basically taking a big whiff of ethanol vapors along with the aromas, and they could cause you to literally pass out.

https://giphy.com/embed/ckFKq9XjhK5ueUAd2u

So what you'll want to do is lift the glass up to your nose as close as is comfortable (more experienced drinkers will be able to basically stick their whole nose in the glass, whereas novices will want to hold it a bit further away) and then take at least a few whiffs before you start sipping — quick whiffs so that they're pleasant rather than sharp. Paterson likens this step to a conversation where you're getting to know the whiskey. This step is all about identifying aromas, so take your time and try to figure out what you're smelling. Are you getting hints of chocolate or tangerines or honey or anything else?

TASTING THE WHISKEY

Holy sh*t people, now is the finally the time for the whiskey to hit your tongue! But as much as you want to, don't just throw it back and feel the burn. Now that you're sipping, you'll want to let the whiskey sit on your palate for around seven or so seconds before swallowing so you can savor all of the various flavors.

According to Paterson, the first sip is really just to cleanse your palate, however. It's the second sip that will really allow you to experience all the flavors the whiskey has to offer. Then there are all the others, and those pretty good too.

https://giphy.com/embed/26tPbQF7OQqv7pztC

WHISKEY STONES

Whiskey stones are cubes — or alternatively shaped objects — made of solid soapstone that can be chilled. Because they're non-porous, and because they don't melt, they can chill your whiskey without diluting it or affecting its flavor. Whiskey stones also stay colder for longer relative to ice.

Glencairn whisky glass. Image: Wikipedia / Amiko82

Second of all, a glass like the Glencairn whisky glass allows you to keep your damn hand away from the whiskey. If you hold the whiskey glass by the bottom of the glass instead of the base, you'll warm up the whiskey, thusly changing its flavor profile. You'll also want to be looking at your whiskey, and you can't do that if your hand is blocking it. So remember, pick a glass that will let you keep the aromas in, and keep your hand out of the picture.

There are, of course, a bunch of other acceptable glasses you can go with, including: the whiskey tumbler (good for whiskey on the rocks and cocktails, shown in the GIF below), the highball glass (allows for plenty of ice and mixer, is preferred in Japan), the snifter (makes you look fancy, but releases a lot of ethanol evaporation due to that wide mouth), and the NEAT whisky glass (a new type of glass that was made by accident at a glass-blowing factory, which happens to direct ethanol vapors away from the nose).

https://giphy.com/embed/mqd2sQsR5fuq4

ON THE ROCKS OR NEAT?

According to Paterson, you basically want to avoid ice in your glass like it's the plague. It chills down the whiskey too much and also dilutes it, subsequently muting some of the flavors. But, if you're willing to defy The Nose, try to keep the ice to a minimum, with just a few blocks. Also aim for blocks that have a relatively small surface area, as that will dilute your whiskey more slowly, but chill it at the same rate as blocks with larger surface areas.

DRINK IT IN WITH YOUR EYES

OK, now that you have your whiskey in your glass, it's time to swirl it around and take a good look at its colors and the way it adheres to the glass. In terms of the color, what you're basically trying to look for are signs regarding the whiskey's aging process.

https://giphy.com/embed/4EF4waRc1Ejth4Iq0V

In general, you'll see whiskeys take on darker colors the longer they've spent in the barrel. This isn't necessarily true in all cases, however, because the barrels vary. For example, Bourbons will take on a darker color over a shorter period of time relative to Scotches because they're being aged in new charred oak barrels that can give away a lot more pigment-affecting compounds. If you're a real expert, you may even be able to determine if caramel coloring has been added. (Also keep in mind that with a whiskey that hasn't undergone any aging, such as some corn whiskeys, you may not see any coloration at all.)

The legs (or tears) of the whiskey — the whiskey that runs down the inside of the glass after you've swirled it — aren't too important for judging quality, but they can tell you a little about the whiskey's texture. If the whiskey has short, slow-moving legs, it'll probably have a thicker texture in the mouth. If it has thinner legs that move relatively fast, that could imply less texture.

ADDING WATER

When you order your whiskey, you'll also want to order a glass or pitcher of distilled water — or even a bottle of water. Why? Because diluting your glass of whiskey just a bit with the right kind of water will drop the ABV, and more importantly, help to bring out all of the flavors. If you have two fingers' worth of whiskey in your glass, try pouring in a couple of thimblefuls of water. Paterson says you want an ABV of about 35% for perfect tasting, although it's hard to say exactly how'd you know that if you're just chilling in a bar with your amigos.

https://giphy.com/embed/oz5mzqTUo4xQtWtXDv

NOSING THE WHISKEY

Now it's time to stick your nose in your glass — and according to Paterson, that means really sticking your nose in there. You want to be very cautious with this step however, as when you stick your nose in a glass of whiskey and take a deep breath, you're basically taking a big whiff of ethanol vapors along with the aromas, and they could cause you to literally pass out.

https://giphy.com/embed/ckFKq9XjhK5ueUAd2u

So what you'll want to do is lift the glass up to your nose as close as is comfortable (more experienced drinkers will be able to basically stick their whole nose in the glass, whereas novices will want to hold it a bit further away) and then take at least a few whiffs before you start sipping — quick whiffs so that they're pleasant rather than sharp. Paterson likens this step to a conversation where you're getting to know the whiskey. This step is all about identifying aromas, so take your time and try to figure out what you're smelling. Are you getting hints of chocolate or tangerines or honey or anything else?

TASTING THE WHISKEY

Holy sh*t people, now is the finally the time for the whiskey to hit your tongue! But as much as you want to, don't just throw it back and feel the burn. Now that you're sipping, you'll want to let the whiskey sit on your palate for around seven or so seconds before swallowing so you can savor all of the various flavors.

According to Paterson, the first sip is really just to cleanse your palate, however. It's the second sip that will really allow you to experience all the flavors the whiskey has to offer. Then there are all the others, and those pretty good too.

https://giphy.com/embed/26tPbQF7OQqv7pztC

WHISKEY STONES

Whiskey stones are cubes — or alternatively shaped objects — made of solid soapstone that can be chilled. Because they're non-porous, and because they don't melt, they can chill your whiskey without diluting it or affecting its flavor. Whiskey stones also stay colder for longer relative to ice.

Whiskey stones Image: Flickr / Srslyguys

HOW TO STORE WHISKEY

Here's the really great news about the logistics of whiskey: Even though you may have to shell out a solid chunk of change for a nice bottle, it's very low maintenance once you have it at home.

As mentioned earlier, whiskey only ages in the barrel, not in the bottle. It can also be opened, and thanks to its high ABV, not spoil or take a hit to quality. You'll still want to store your whiskey in a dark place, out of direct sunlight, as the heat could negatively affect the flavor.

Whiskey stones Image: Flickr / Srslyguys

HOW TO STORE WHISKEY

Here's the really great news about the logistics of whiskey: Even though you may have to shell out a solid chunk of change for a nice bottle, it's very low maintenance once you have it at home.

As mentioned earlier, whiskey only ages in the barrel, not in the bottle. It can also be opened, and thanks to its high ABV, not spoil or take a hit to quality. You'll still want to store your whiskey in a dark place, out of direct sunlight, as the heat could negatively affect the flavor.

THE FUTURE OF WHISKEY

It seems that the future of whiskey most likely lies in the expansion of current whiskey markets, the establishment of producers in nations not previously considered top-tier players in whiskey — such as Germany, Australia, and India — and one form or another of "rapid aging." As far as growth throughout the world, things are looking extremely bright for the future of whiskey. The whiskey market in the U.S. grew to $3.4 billion in 2017, with domestic production volume increasing to 23.2 million cases. Worldwide, the whiskey market is expected to be valued at about $7.4 billion by 2023, with a big hand from a burgeoning middle-class market in China. Millennials are also apparently driving growth in the whiskey market, displaying a preference for high-end and super-premium Scotches. https://giphy.com/embed/5t0xYFPAtY2KdlKB5L In regards to rapid aging, that seems like it could go either way right now. That is, it could explode in popularity, or die out completely. If it does catch on, we're basically looking at a few different options for how to fast-age whiskey, including: using much smaller barrels, oak infusion spiral systems, or even "sonic aging" methods — a.k.a. music. SMALLER BARRELS Using smaller barrels is probably the least heretical way out of the three to speed up the aging process, as the proponents of this method point out that using smaller barrels simply increases the rate at which the ethanol chunks off flavor compounds from the barrel thanks to there being less volume that needs to be infused with flavor compounds. Some companies are even going so far as to simply make thermos-like containers out of oak, which could age — or at least add lots of flavor — to whiskey in just a matter of a few days. THE OAK INFUSION SPIRAL The oak infusion spiral is another pretty low-tech product that aims to achieve barrel-aged flavors over the course of a few days. The infusion spiral, which looks like a tall stack of wooden coins all stuck together, works by being placed in your container of whiskey so it can interact with the ethanol and give up some of its flavor compounds. The spiral shape also allows for the whiskey to penetrate the oak much more efficiently than it would in a barrel; the grain direction of barrels is such that the whiskey comes into contact with it at a perpendicular angle, as opposed to the infusion spirals, which allow the whiskey to pass through its membrane top to bottom. (If whiskey barrels didn't have the grains of their wood sides moving in the direction they do, the oak would absorb too much liquid and they would start leaking.) https://giphy.com/embed/1Yc5oWuVG3TUvn4GbX PRESSURIZED CONTAINERS AND SONIC AGING Finally, there's the really sci-fi aging techniques that use pressure aging and/or sonic aging. Basically, with pressure aging, you're talking about sticking the distilled grain alcohol in a giant steel container with a bunch of tiny oak barrel chunks. After you've done that, you apply force to the steel container — squeezing and expanding it — thusly forcing the distilled alcohol into and out of the barrel chunks so it can quickly pick up their flavor compounds. Like the oak infusion spiral, this is another case of "putting the barrel in the whiskey" rather than putting the whiskey in the barrel, and Cleveland Whiskey, a pioneer in this field, says it can go from distilled alcohol to bottled whiskey in one week flat. https://giphy.com/embed/fQx9ChYYZhqygZq14D With sonic aging, it seems that folks are basically just setting up big-ass sound systems in their warehouses, and letting bassy music vibrate the hell out of the casks in the hopes that all that movement will cause the whiskey to pick up flavor compounds from the barrels more quickly. That literally seems to be the long and short of this strategy. OUR FAVORITE WHISKEY DRINKS Now that all your whiskey knowledge is in order, take some time to check out a handful of our favorite whiskey drinks. And while yes, some may think it's a complete dishonor not to drink your whiskey untainted by other ingredients, we think these classic cocktails would earn the approval of even the most staunchly conservative whiskey aficionados — maybe even The Nose himself. 1. APPLE CIDER SLUSH 2. APPLE JACK JELLO SHOTS

2. APPLE JACK JELLO SHOTS

3. BIG BEAR SOUR

3. BIG BEAR SOUR

4. DIRTY ROCKY ROAD MILKSHAKE

4. DIRTY ROCKY ROAD MILKSHAKE

5. HAWTHORN PARK

5. HAWTHORN PARK

6. HOT CANDY APPLE

6. HOT CANDY APPLE

7. OLD FASHIONED

7. OLD FASHIONED

8. PORTOFINO

8. PORTOFINO

9. THE FORBIDDEN

9. THE FORBIDDEN

10. WHISKEY SMASH

10. WHISKEY SMASH

All GIFS: Giphy

Original Tipsy Graphics: Shina Kim-Avalos

Independence Day Drinks

4th Of July All American Jello Shots

4th Of July Cake Vodka Milkshake

4th Of July Diversity Bomb Shot

4th Of July Jello Shots

4th Of July Layered Shots

4th Of July Pop Rocks Martini

4th Of July Raspberry America

4th Of July Spiked Bomb Pops

4th July Popsicle Margarita

4th July Edible Shot Glasses

4th July In A Bottle

All American Daiquiri